Appreciating Japanese (?) Metalwork

Many objects passed through my hands as I slowly emptied my mother’s house in 2018.

Some were mundane, worn-out, or just plain dumpster-worthy. Others were worthy of awe.

My time with most of the beautiful ones was brief, as they had to be sold.

But I keep them with me in virtual form as photos on my I-phone. This lets me savor them little by little, while remembering that my mother’s love of beautiful objects is part of why I became an artist.

My mother had a very fine eye. She decorated our house with beautiful objects from many countries - especially from China, Korea and Japan. Art gave Mom an escape from the demands of being a wife and mother.

She didn’t have much of an art-buying budget. But she made what she had go a very long way. I remember early trips to Chinatown on Chicago’s south side, back when its antique shops were full. I wish I could enter those shops again now - with prices still set at 1960’s levels. I would purchase the tall bronze pagoda that stood in the front window of one of the shops. I’d listen again as the clerks spoke Mandarin to one another. I’d buy more of the Japanese woodblock prints my mother loved, on sale at another shop. She only bought one print by Hiroshige, and always regretted she didn’t buy more. I remember how upset Mom was when the antique shops closed. Driven out of the neighborhood, Mom said, by people who wanted their land - and broke their shop windows multiple times.

Mom also had a set of antique metal plaques. Ten in all, small, measuring no more than 13” on a side. Made of copper, brass or bronze, and a silver metal that might be nickel silver or some kind of steel. Patinas or gold leaf might have been applied to some of the plaques.

The plaques were formerly attached to an antique wood etagere carved with Asian motifs. I always assumed the etagere was Chinese. Standing on its own matching bench, the etagere measured about 9 feet tall.

Only one of the plaques remained attached to the etagere in 2018, when I had to disassemble the unit. I’d hardly touched it when the plaque fell into my hands, so tenuous was its position. A few of its small motifs fell off too.

The other plaques were stacked on one of the shelves.

I don’t remember Mom talking about the etagere or the metal plaques. I’m guessing she planned to re-attach the plaques some day, because she loved restoring old things. I could ask still ask her, of course - but would she remember? Would such a memory trouble her now?

All of the plaques show signs of wear. Motifs have gone missing. Spots have appeared.

Mom was never bothered by flaws in a piece. As far as she was concerned, they did not affect its soul.

Most of the plaques feature motifs drawn from the natural world such as birds, trees, and flowers. All have symbolic resonance in Asian culture. One plaque features what looks like a hanging basket, another, a vase. All of the plaques juxtapose 2- and 3-dimensional motifs, with the former serving as backdrops for the latter.

When I showed the plaques to my friend Kiff, a fellow metalsmith, she agreed that they looked Japanese. Because Japanese metalwork has a certain look to it. Masterful. Quiet. Refined.

We thought of tsuba, the metal sword guards made in Japan in the 17th to 19th centuries. Books have been written about the glories of tsuba. Museums have built collections. A Google image search for tsuba yields extraordinary old examples - as well as modern reproductions.

(Of course, we could be wrong. It’s possible that Chinese or other metalsmiths made these pieces.)

Admiring how elegantly the birds on the plaques were rendered, Kiff and I could only guess at the metalworking technique used to make them and the other 3-dimensional motifs.

Was it repousse - meaning a piece of sheet metal was painstakingly hammered from behind into a bowl of pitch until the bird form began to take shape? As metalworking techniques go, repousse is pretty demanding. Neither Kiff nor I has practiced it.

Or were the 3-dimensional motifs hammered into a mold? So outcomes were pre-determined?

Or, easier still, stamped by a powerful die?

Strangely, while the 3-dimensional motifs seem finely finished, other aspects of the plaques are hastily rendered.

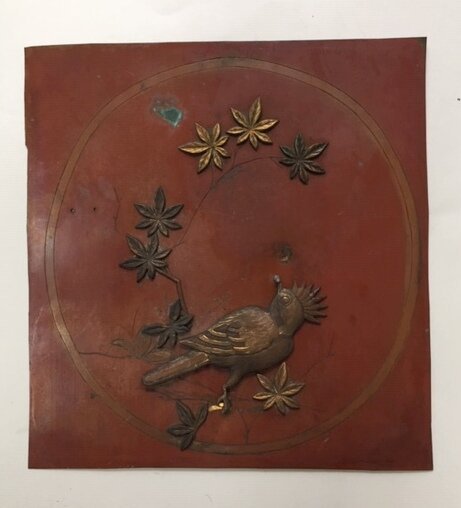

For example, the prongs that attach the 3-dimensional motifs to the plaques are rather crude. After running through holes in the plaque, the prongs bend sharply to hold the motifs in place, which studs the back of the plaques with unsightly irregularities. Granted, the backsides would not normally be seen. A more serious concern is that over time, the prongs break, causing the motifs to slide out of place.

To take a second example of hasty production, edges on some of the plaques are uneven, as if the sheet metal was cut with a scissors or shears. Corners on some of the plaques are sharp. Maybe the perimeters of the plaques didn’t matter? Were they, like the prongs, hidden from view?

And a third example: some of the motifs are rendered with incised or acid-etched lines. These 2-dimensional motifs feel like quick sketches, present only to create an illusion of depth or perspective or to provide a backdrop for the more fully-realized motifs. The incised lines appear to be drawn by hand without a ruler. However, given that the niches in the etagere are so deep, and the plaques were displayed on the back walls of the niches, these shortcuts of time and effort make sense.

In sum, it seems these plaques were made for commercial purposes, perhaps at significant scale.

Somewhere in the world there is an expert who knows the answers.

I’d love to know who that person is.

In the meantime, I post rudimentary images of the plaques here with basic descriptions.

In times such as these, when a pandemic threatens, we all need a little escape.

Thank you, Japanese metalworkers.

(And thank you too, Mom.)

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

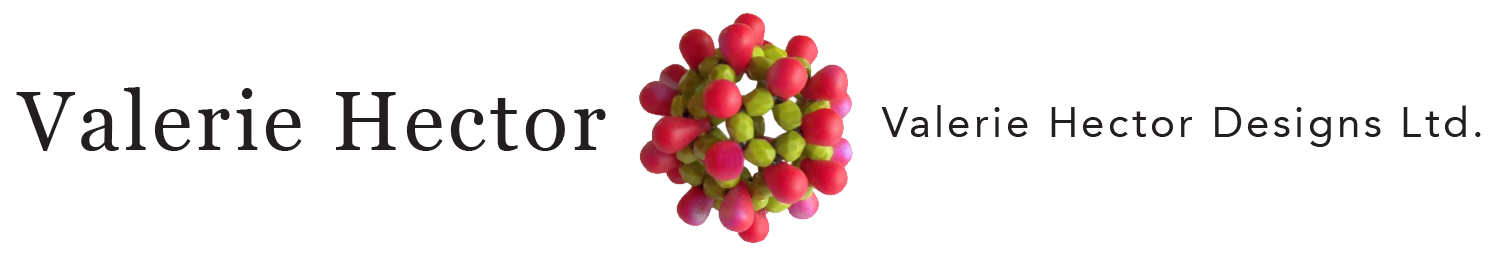

The first plaque (below) seems fully intact. A hanging vase filled with flowers and leaves fills the upper register as a small bird swoops by below, over a lattice-filled ground. Patinas or gold leaf might have been used on some of the 3-dimensional motifs - such as the golden hanging leaves and fronds, which retain a very bright luster. The metal sheet appears to be about 20 gauge. Dimensions: 9 1/8” wide by 10 3/4” tall.

Judging by holes in the second plaque (below) it’s missing a half dozen or more motifs. Yet the major motifs remain: a crane in flight behind a vase filled with chrysanthemum, iris and prunus flowers. No doubt their combination here may have symbolic associations. The vase sits somewhat off-kilter, an artifact, perhaps, of a poorly-situated prong. In the lower left corner, a rectangular lattice motif is incised or acid-etched into the metal, lending a sense of depth and perspective. The metal sheet appears to be about 20 gauge. Dimensions: 10 1/8” wide by 9” tall.

The third plaque (below) features a bird paused at the edge of a stream under a flowering (prunus?) tree branch. Uneven gold-colored patches suggest places where 3-dimensional motifs have gone missing. Was gold (or bright brass or bronze) the original background color? Or an artifact of a gilding or patina-adding process? The sheet metal appears to be about 20 gauge. Dimensions: 10 5/8” wide by 5 7/8” tall.

The fourth and fifth plaques (below) seem to form a pair made of copper, brass or bronze and possibly nickle silver. One plaque features a bird in flight above a flowering prunus branch, the other, a bird paused on a similar branch. The flowers are rendered in several colors. The plaques are unevenly cut from sheet that might be as thin as 22 gauge. Dimensions: 4 3/4” wide by 10 3/4” tall.

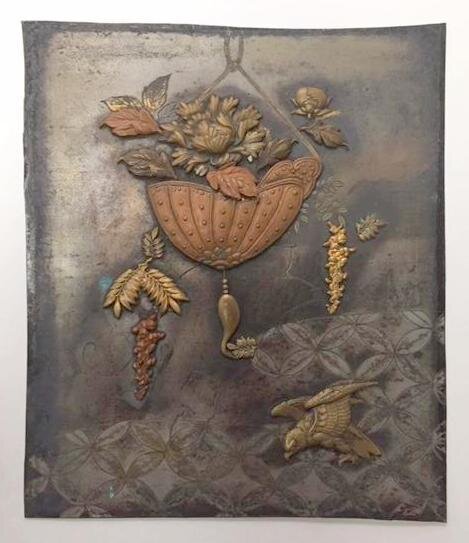

The sixth plaque (below) features a circular shape in the background, possibly a sun or moon motif. The motif is rendered with incised lines imperfectly drawn as if by hand. A bird (kingfisher?) surrounded by a leafy branch gazes upward as if looking at the orb. Originally attached with two prongs, the bird had been reduced to one prong by the time I came along. It kept slipping out of position. Suddenly, as I was photographing this plaque, the bird broke off in my hand. It is made from metal less than half a millimeter thick. The plaque’s sheet metal has roughly-cut edges. Dimensions: 7 3/4” wide by 8 1/8” tall.

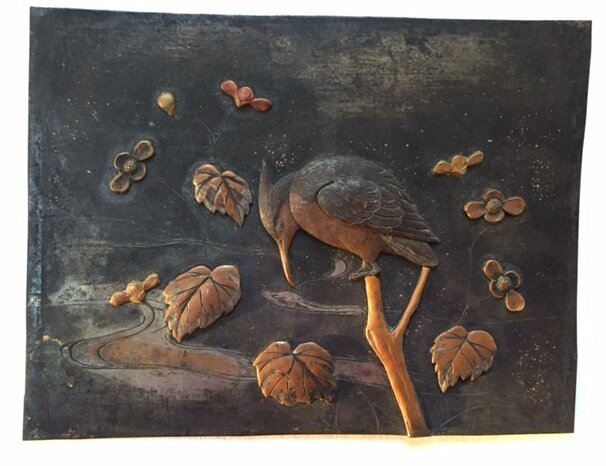

The seventh and eighth plaques (below) seem to form a pair. Number seven (top row) shows a bird (a woodpecker?) standing on a branch while gazing down towards a flowing stream. Flowers and leaves swirl in the air around the bird as if a sudden gust of wind has picked up. The eighth plaque (bottom row) shows a bird flying through floating leaves above a silvery stream. On the backside of each plate, silvery lumps of base-metal solder are visible where prongs have been repaired. The sheet metal looks to be 20 gauge and crudely cut. Average dimensions: 7” wide by 5” tall.

The ninth plaque (below) features a chrysanthemum or other flower accompanied by 2- and 3-dimensional leaves. This minimally-decorated plaque might have been meant for the lowermost niche in the etagere, one too low to be seen very often. Dimensions: 12 7/8” wide by 3 1/4” tall.

In the tenth plaque (below), a small bird soars up from a leafy branch. A large circular motif in the background suggests a sun or moon. Ten empty holes int he plaque indicate missing 3-dimensional motifs. Two of the corner areas are stained with a dark substance - possibly from some kind of glue. Dimensions: 5 3/4” wide by 5 3/4” wide.